The twisted nanotubes that tell a story

- Dec 9, 2025

- 3 min read

In collaboration with scientists in Germany, EPFL researchers have demonstrated that the spiral geometry of tiny, twisted magnetic tubes can be leveraged to transmit data based on quasiparticles called magnons, rather than electrons.

Magnonics is an emerging engineering subfield that targets high-speed, high-efficiency information encoding without the energy loss that burdens electronics. This energy loss occurs when electrons flowing through a circuit generate heat, but magnonic systems don’t involve any electron flow at all.

Instead, an external magnetic field is applied to a magnet, upsetting the magnetic orientation (or ‘spin’) of the magnet’s electrons. This upset enables a tailored collective excitation called a spin wave (magnon), which travels through the magnet – like a ripple travels across a pond – while the electrons themselves stay put.

Despite the advantage of no electron flow, three-dimensional (3D) magnonic systems remain largely experimental, because they typically require strong magnetic fields or extremely low (cryogenic) temperatures that make them incompatible with mainstream devices.

Now, researchers in the Lab of Nanoscale Magnetic Materials and Magnonics (LMGN) in EPFL’s School of Engineering have taken magnonics a big step closer to toward real-world application by simultaneously eliminating the need for extreme temperatures and presenting a 3D fabrication methodology. By physically twisting nanoscale tubes made of ferromagnetic nickel, the team induced a special property called chirality, in which the symmetry of an object differs from that of its mirror image. This asymmetry caused magnons to only flow in one direction along a tube’s axis, creating a crucial opportunity to encode binary information and transmit signals on a chip. For example, the pattern of magnon flow detected in a ‘right-handed’ spiral twist might represent 0, while in a left-handed one it might represent 1.

LMGN head Dirk Grundler says that the engineering feat also creates a diode, a key component of electronics technologies that conducts signals only in one direction. “Essentially, we have created a 3D diode for magnons that, at the same time, can encode data at room temperature.” The research has been published in Nature Nanotechnology.

Fully compatible and mass-producible

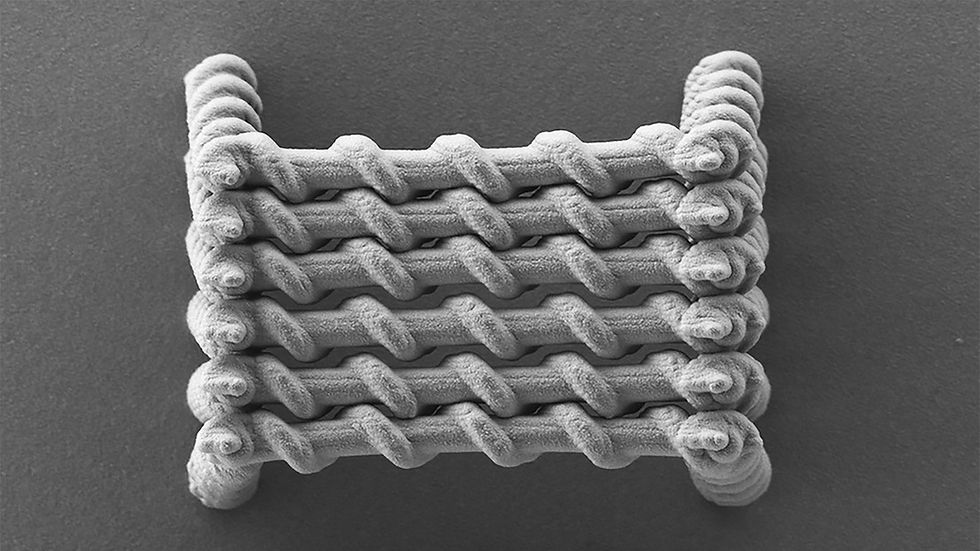

The team’s nanoengineering process, pioneered by Huixin Guo and former LMGN researcher Mingran Xu, involves 3D-printing a twisted polymer rod and coating it with an extremely thin layer of nickel. While some materials spontaneously exhibit chiral properties at cryogenic temperatures, the EPFL scientists found, thanks to X-ray imaging experts at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids and the BESSY II synchrotron facility in Germany, that their geometry-based approach resulted in a stronger chiral effect than any observed in nature. Simulations and theoretical calculations suggest that shrinking the tubes and tweaking their spiral curvature could further enhance this effect.

“We are the only group in the world that can produce these structures out of nickel, which does not naturally possess chiral properties. Therefore, we essentially ‘imprint’ chirality using 3D geometry alone,” summarizes LMGN researcher Axel Deenen.

Their fabrication process, which can be used to mass-produce the ferromagnetic tubes, is fully compatible with mainstream chip technology used in the microelectronics industry – no strong magnetic fields, special materials, or extreme temperatures required. Although a magnetic field is used to ‘program’ the tubes and spin waves, this magnonic information is stored without any moving charge, making it a stable and nonvolatile encoding method.

Grundler adds that looking into the future, the work could facilitate the uptake of magnonics technology as a driver of neuromorphic, or brain-inspired, computing for artificial intelligence. “Hardware-implemented neuromorphic computing is key for optimizing AI applications, but like the brain, this only makes sense in terms of 3D architectures and low energy consumption. Our technology is now ready to support this.”

Reference Geometry-induced spin chirality in a non-chiral ferromagnet at zero field

Mingran Xu, Axel J. M. Deenen, Huixin Guo, Pamela Morales-Fernández, Sebastian Wintz, Elina Zhakina, Markus Weigand, Claire Donnelly & Dirk Grundler

Comments